Syllable Position Prominence in Unsupervised Neural Network Segment Categorization

Syllable Position Prominence in Unsupervised Neural Network Segment Categorization

- Fengyue Zhao, Sam Tilsen. Syllable Position Prominence in Unsupervised Neural Network Segment Categorization. LabPhon 19. June 27 - 29 2024. Hanyang University, Seoul, South Korea.

English obstruents exhibit diverse phonetic realizations across syllable positions, like /t/ and /p/ in words such as top and pot [1]. Linguistically we assume that phone identity—(e.g. /p/ vs. /t/) is a strong predictor of representational similarity, while syllable position—e.g. onset vs. coda—is perhaps a secondary factor. But is this always the case? Unsupervised learning in neural networks presents a practical approach for exploring this interplay, because it does not require presuppositions about phonological categories such as segments and syllable. Previous studies [2, 3] have demonstrated the capacity of neural networks to learn abstract representations from acoustic signals. This study employed an unsupervised autoencoder neural network to explore the correlation between phonological categories and network-learned representations. Surprisingly, we found that for consonants, syllable position plays a larger role in representational similarity than phone identity.

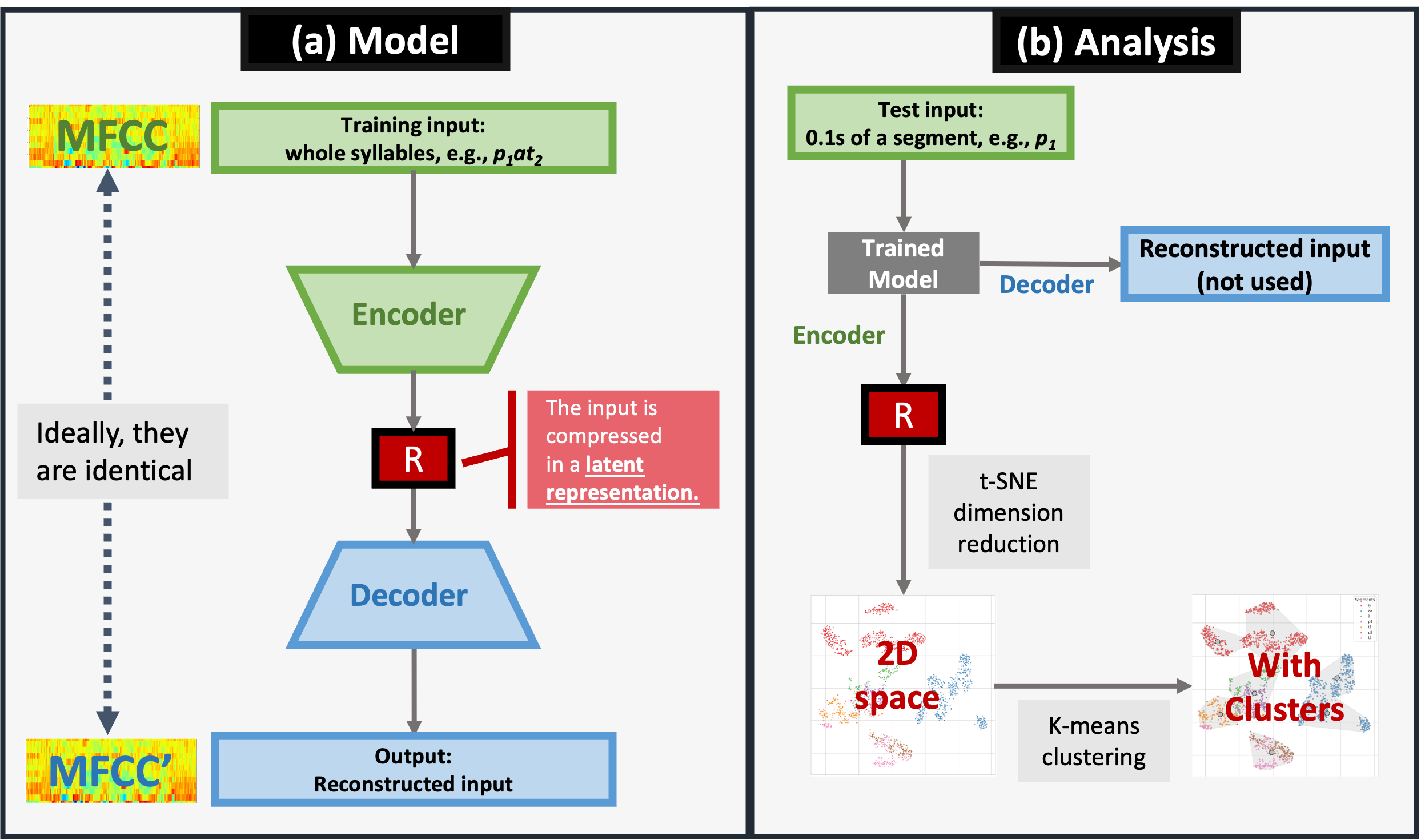

Method: Data: In order to enhance the interpretability of neural models, we chose to use a controlled experimental dataset to investigate the interplay between syllable position and segment identity. The dataset comprised nine syllables corresponding to all combinations of {p, t, Ø}onset × /a/ ×{p, t, Ø}coda (note that onset Ø was realized as glottal stop [ʔ]), with /p/ and /t/ appearing in onset position (denoted as p1 and t1) and coda position (p2 and t2). Examples included [p1at2], [ʔap2], etc. The syllables were articulated following an initial prolonged [i]. Model: The autoencoder architecture [2] (see Fig. 1a) encompassed an encoder compressing acoustic input into a latent representation (labeled R) and a decoder reconstructing the input. The inputs were 12-coefficient MFCC vectors (window: 25ms hamming, hop time: 1ms, range: 0 - 8000 Hz). Notably, the autoencoder acquired a compact representation of the input in the latent representation R, without utilizing explicit labeling during training. The data were divided into training (60%), validation (20%), and test sets (20%). Analysis: During testing, all 7 individual categories (i.e., aa, iy, ʔ, p1, t1, p2, t2) were fed into the autoencoder model. Subsequently, extracted latent representations (patterns of node activation in R) were subjected to dimensionality reduction via t-SNE (t-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding), followed by K-means clustering to assess activation pattern similarities within the R space (Fig. 1b).

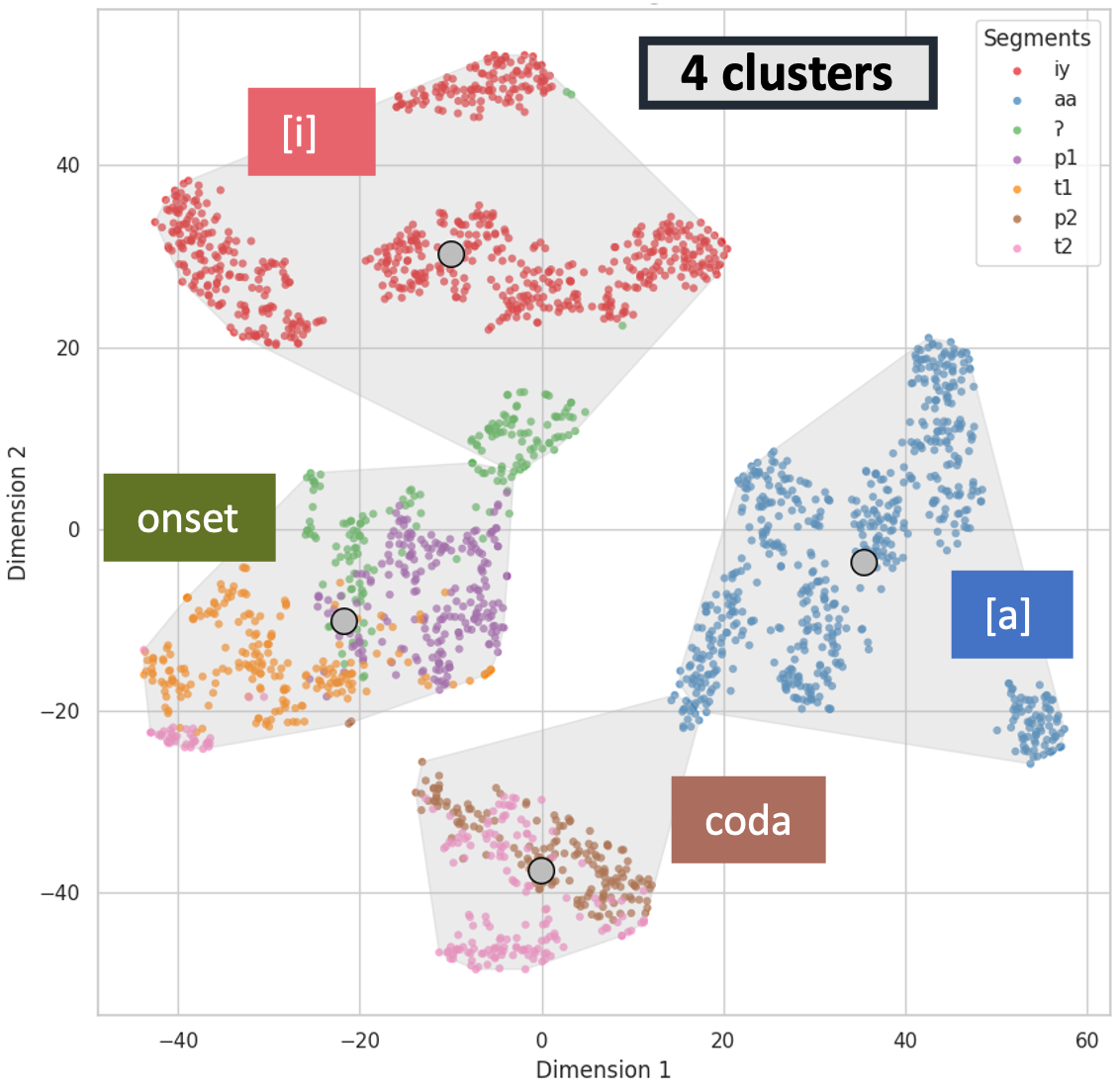

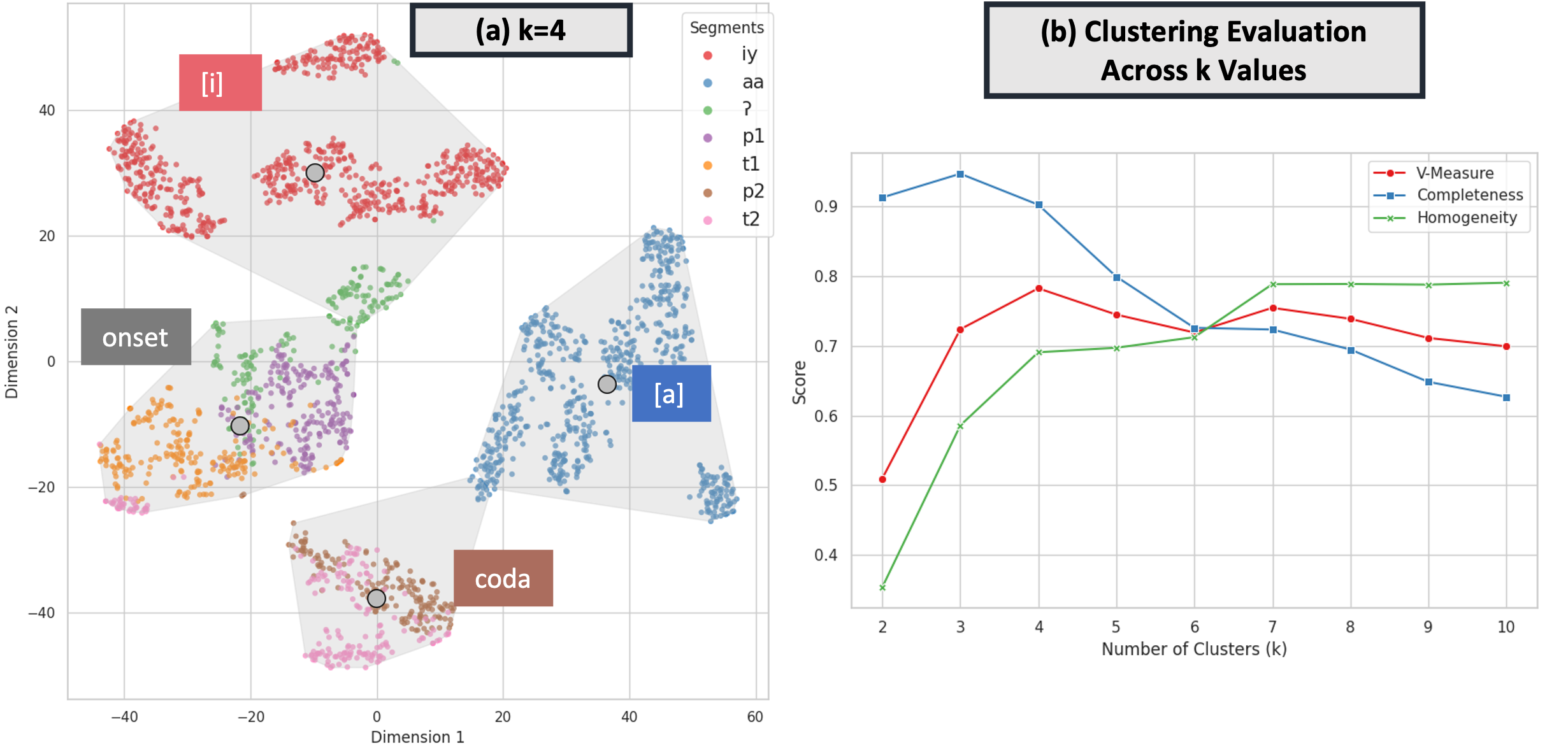

Results: For consonants, syllable position emerged as a stronger predictor of representational similarity than segment identity. In Fig. 2a, consonants sharing the same syllable position but different identities (e.g. onset p1, t1, ʔ) were closer to each other in the representation space compared to consonants of the same identity in different positions (e.g. onset p1 and coda p2). This observation was further supported by the k-means clustering result. Fig. 2a shows the locations of individual segment tokens in representational space, along with grey convex hulls surrounding clusters. With k=4 clusters, k-means algorithm effectively separated the two vowels [i] and [a], while also forming clusters of onset sounds (p1, t1, and ʔ) and coda sounds (p2, t2). Certain instances of glottal stops [ʔ] were grouped with [i]’s, potentially explained by varied phonetic realizations — some as full glottal plosives while others may exhibit creakiness. Sub-clusters for [i] and [a] were associated with individual speakers. The k=4 clustering achieved strong performance metrics (V-Measure: 0.78, Completeness: 0.90, Homogeneity: 0.69) compared to other values of k. Fig. 2b shows that increasing the cluster count does not lead to distinct clusters associated with segment identity. The V-measure score, a harmonic mean between completeness and homogeneity, was in fact maximal for k=4, suggesting that separating onsets and codas provides the optimal clustering of sound categories.

Figure 2. (a) K-means clustering result when k=4. This illustration shows the locations of individual segment tokens in representational space R, along with grey convex hulls surrounding clusters. The boxed annotations summarize the 4 clusters: [i]’s, [a]’s, onsets, and codas. (b) Evaluation metrics (V-Measure, Completeness, Homogeneity) of k-means clustering across k values (2 to 10), illustrating performance fluctuations with cluster count.

Conclusion: Our results show that syllable position is more influential than segment identity in representational space learned by the neural network from acoustic signals. This is important because it suggests that the role of syllable position in human representations may be underappreciated. Future exploration of this finding with larger datasets will be of value.

References

[1] Turk, A. (1994). Phonological Structure and Phonetic Form: Articulatory phonetic clues to syllable affiliation: gestural characteristics of bilabial stops.

[2] Shain, C., & Elsner, M. (2019). Measuring the perceptual availability of phonological features during language acquisition using unsupervised binary stochastic autoencoders. Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, 69–85.

[3] Shain, C., & Elsner, M. (2020). Acquiring language from speech by learning to remember and predict. Proceedings of the 24th Conference on Computational Natural Language Learning, 195–214.